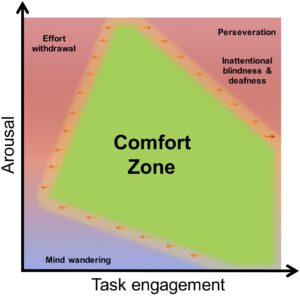

I recently co-authored this paper on mental workload with colleagues at ISAE-AERO from Toulouse. Frederic Dehais invited me to contribute to a paper that he had under development, which was based around the diagram you can see above this post.

I was very happy to be involved and have an opportunity to mull over the topic of mental workload and its measurement, which has always long been an equal source of interest and frustration. Back in the 1990s sometime, I remember a conference presentation where the speaker opened with a spiel that went something like this – ‘when I told my bosses I was doing a study on mental workload, they said mental workload? Didn’t we solve that problem last year?’ Well, nobody had solved that problem that year or any other year since, and mental workload remains a significant topic in human factors psychology.

The development of psychological concepts, like mental workload, traditionally proceeds along two distinct lines or strands, these being theory and measurement or testing. This twofold approach was certainly true of the early days of mental workload in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when resource models of human information processing were rapidly evolving and informing the development of multidimensional workload measures drawn from subjective self-report, performance and psycho/neuro-physiology. But as time passed, mental workload research developed a definite bias in the direction of measurement at the expense of theory. This shift is not that surprising given the applied nature of mental workload research, but when I read this state-of-the-art review of mental workload published in Ergonomics five years ago, I couldn’t help noticing how little had changed on the theoretical side. The notion of finite capacity limitations on cognitive performance still pervades this whole field of activity, but deeper questions about these resource limits (e.g., what are they? What mechanisms are involved?) are rarely addressed. This is a problem, especially for applied work in human factors, because it becomes difficult to draw inferences from our measures and make solid predictions about performance impairment that go beyond the obvious.