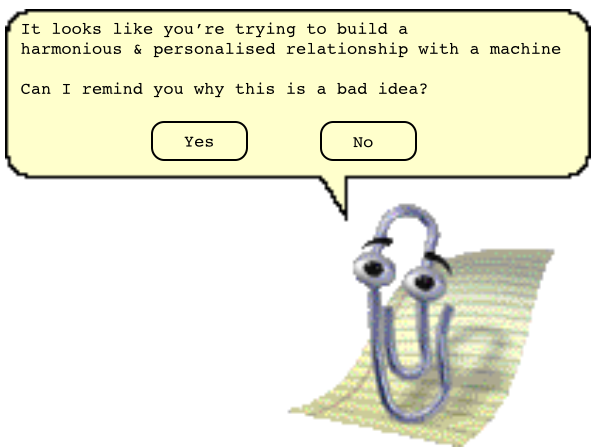

Everyone who used MS Office between 1997 and 2003 remembers Clippy. He was a help avatar designed to interact with the user in a way that was both personable and predictive. He was a friendly sales assistant combined with a butler who anticipated all your needs. At least, that was the idea. In reality, Clippy fell well short of those expectations, he was probably the most loathed feature of those particular operating systems; he even featured in this Time Magazine list of world’s worst inventions, a list that also includes Agent Orange and the Segway.

In an ideal world, Clippy would have responded to user behaviour in ways that were intuitive, timely and helpful. In reality, his functionality was limited, his appearance often intrusive and his intuition was way off. Clippy irritated so completely that his legacy lives on over ten years later. If you describe the concept of an intelligent adaptive interface to most people, half of them recall the dreadful experience of Clippy and the rest will probably be thinking about HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. With those kinds of role models, it’s not difficult to understand why users are in no great hurry to embrace intelligent adaptation at the interface.

In the years since Clippy passed, the debate around machine intelligence has placed greater emphasis on the improvisational spark that is fundamental to displays of human intellect. This recent article in MIT Technology Review makes the point that a “conversation” with Eugene Goostman (the chatter bot who won a Turing Test competition at Bletchley Park in 2012) lacks the natural “back and forth” of human-human communication. Modern expectations of machine intelligence go beyond a simple imitation game within highly-structured rules, users are looking for a level of spontaneity and nuance that resonates with their human sense of what other people are.

But one of the biggest problems with Clippy was not simply intrusiveness but the fact that his repertoire of responses was very constrained, he could ask if you were writing a letter (remember those?) and precious little else.