From the point of view of an outsider, the utility and value of computer technology that provides emotional feedback to the human operator is questionable. The basic argument normally goes like this: even if the technology works, do I really need a machine to tell me that I’m happy or angry or calm or anxious or excited? First of all, the feedback provided by this machine would be redundant, I already have a mind/body that keeps me fully appraised of my emotional status – thank you. Secondly, if I’m angry or frustrated, do you really think I would helped in any way by a machine that drew my attention to these negative emotions, actually that would be particularly annoying. Finally, sometimes I’m not quite sure how I’m feeling or how I feel about something; feedback from a machine that says you’re happy or angry would just muddy the waters and add further confusion.

Speaking as someone who is generally sympathetic to this category of technology, I feel that the third argument is the strongest one. Emotional experience does not always require explicit emotional labeling. On the other hand, machine classification may struggle to define the type of physiological activity accompanying such a diffuse emotional state – so this may not be an issue if physiological computers are concerned with more extreme or clearly differentiated states. The second point is really aimed at interface design. This is a tough one from the perspective of providing feedback in a way that is unobtrusive, private and would not amplify a negative emotional state. Designing an interface for anger detection and feedback is a tough challenge. Even bad ideas like flashing red letters reading “CALM DOWN” may be only marginally worse than an adaptive avatar who switches to a soft sympathetic voice when the user becomes particularly irate.

The first argument is the one I would like to tackle in this particular post. In this context, physiological computing is concerned with capturing those psychophysiological correlates of anger or frustration. It is important to note that physiological correlates of a particular emotional state, like anger, are not synonymous with the actual experience of anger. The physiological response may include elements such as elevated blood pressure or small changes in cardiac output (the volume of blood expelled by the heart), which are imperceptible from a subjective perspective. Furthermore, there seems to be a link between the experience of negative emotions, such as anger and particularly anxiety, and coronary heart disease (see abstract from this 2000 review). It is entirely reasonable to assume that health implications of negative emotion are mediated by physiological changes. Furthermore, we may not be aware of these physiological changes because they occur below the level of conscious introspection; there is at least one theory that unconscious processes drive physiological changes in response to worry and rumination.

In my view, physiological computing has at least two contributions to make in this domain. First of all, to unmask changes in physiology due to negative emotion that may take occur subconsciously. Also, to quantify the level or magnitude of physiological change that associated with an emotional stimulus or ongoing situation. This process of revelation and quantification is almost identical to the process of biofeedback, which works as a therapeutic intervention by informing the development of strategies for coping and self-regulation. It has been hypothesised (by Prof. Rosalind Picard) that affective feedback from computer technology has similar potential to promote positive strategies for self-regulation, i.e. reducing the impact of negative emotion on health. I would also argue that physiological computer systems are the best means to achieve this end result; like biofeedback technology, this approach captures anger and other negative emotions via the physiological activity that is at the root of any detrimental effects on health. See this earlier post for more on that theme and this one for an example of a system designed to reduce stress by providing biofeedback to a mobile device.

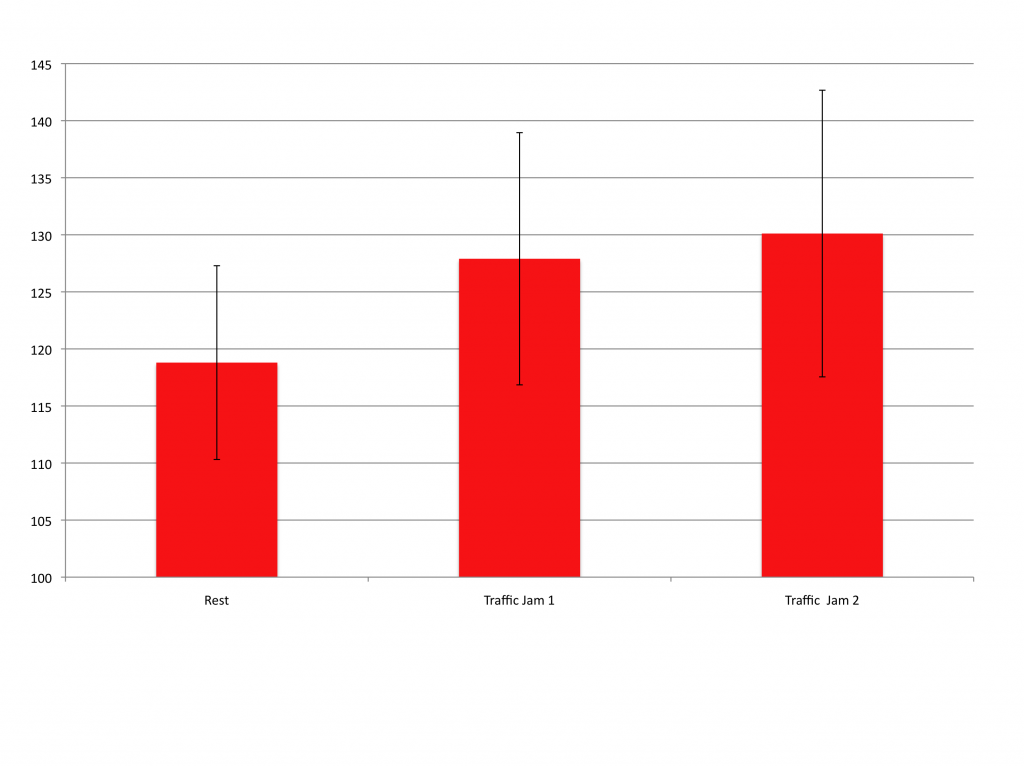

My basic point is this – we all know what it feels like to be angry but we have no idea how our current level of anger may be affecting the autonomic nervous system (and our health in the longer term). Perhaps if we have some quantification of this experience, it might change the way we choose to manage our anger. A current PhD student of mine, Elena Spiridon, has been looking at cardiovascular and EEG correlates of anger with this basic hypothesis in mind. The first thing we learned was that it is really tough to (ethically) induce genuine anger in the laboratory – we used a combination of a rude experimenter plus a malfunctioning computer to irritate people but this was not as effective as we had hoped. We went back to the drawing board and came up with a different approach. We reasoned that our lab task was too sterile and there were no real consequences of poor performance due to the malfunction. Therefore, we went to our driving simulator, reasoning that this was a more realistic type of task and came up with the following scenario. You are asked to complete a 15min journey in the simulator, the purpose of this journey is to collect a child from school so you cannot be late. We told our participants that they would lose their payment for taking part in the study if they did not complete the journey in time (to add some real-world consequences). Then we stuck two traffic jams in the simulated drive – the first occurred early in the journey (i.e. it was a delay but the driver could still make up for lost time) and another one just before the end (i.e. it was now impossible to make the journey on time). Our simulator scenario was much more effective at inducing anger based on the subjective questionnaires we used. We also found significant and substantial increases in systolic blood pressure when people were stuck in the traffic jam. The figure below shows a bar chart for 20 male participants at baseline (before the drive) and at the early traffic jam (1) and the late traffic jam (2).

As you can see, increased blood pressure during the traffic jams was substantial – obviously this was a simulated environment, so we might expect even larger increases in the field. If we could see how everyday stresses and hassles, like traffic jams, affected our cardiovascular health via technology – would this alter how we cope with these situations? Would we be able to take a deep breath and calm down? I think this approach has real possibilities for alleviating the impact of anger and stress on long-term health.

As you can see, increased blood pressure during the traffic jams was substantial – obviously this was a simulated environment, so we might expect even larger increases in the field. If we could see how everyday stresses and hassles, like traffic jams, affected our cardiovascular health via technology – would this alter how we cope with these situations? Would we be able to take a deep breath and calm down? I think this approach has real possibilities for alleviating the impact of anger and stress on long-term health.

But designing an effective interface for an anger-detection system in the vehicle is still a tough one…

Footnote: for anyone concerned about the ethics of our experiments, we always paid our participants the full amount regardless of the fact that they were late for their simulated school pick-up. The instructions contained some deception in order to make the anger manipulation work.